The “debate of the century” was on capitalism, Marxism, and happiness. This essay aims to compare the points of these two viral intellectuals to the Islamic tradition.

On April 19th, I and over three thousand others went to the Sony Centre in Toronto to see a debate between Dr. Jordan Peterson and Dr. Slavoj Zizek. The sold-out “debate of the century” was meant to tackle “Happiness: Capitalism vs Marxism”, though neither speaker studied economics academically.

The debate became more of a discussion, with the speakers agreeing on some points, but talking passed one another on others. Peterson acknowledged Zizek’s originality, and Zizek mentioned that both speakers were shunned by academia’s liberal establishment.

I was first exposed to the works of Zizek and the classes of Peterson in 2011 during my undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto. Zizek’s books were quite dense for me; and I had heard that Peterson’s courses were a mix of psychology, evolutionary biology, pop culture, and mythology. Both are intelligent, eccentric thinkers who do not fear controversy, and so I have long desired a discussion between them.

At the outset of the debate, Peterson mentioned that tickets to the event were being scalped online for a higher price than the Toronto Maple Leafs playoff game taking place on the same night.

This is good: in the age of YouTube and podcasts, intellectual inquiry is an emerging form of entertainment with its own girth. On the other hand, the event’s popularity reflected a sense of Canadian passive-aggressiveness. While our culture is stereotypically polite and politically-correct, we are just as opinionated as anyone else on the planet; and that was reflected in the immature level of heckling, cheering, laughing, and scoffing at the debate, making it feel more like a sporting event.

I re-watched the debate on YouTube and took notes. As a political science graduate and a student of Islam, I wanted to delineate what I feel is an Islamic response to some of the points highlighted in the discussion.

Jordan Peterson

Jordan Peterson’s speech was a ten-point critique of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto. A take on Das Kapital or even Zizek’s works would have been far better suited for an event of this nature, as the Manifesto was essentially a political pamphlet rather than a fleshed-out magnum opus. Still, many of his points highlighted communism’s inherent problems from a liberal individualist perspective.

Peterson correctly pointed out that Marxism views history primarily as a class struggle. The Islamic dialectic – if I could borrow the term from Hegel and Marx – would view history primarily from an ethical lens. The portion of the Qur’an that is dedicated to history does not mention many names, places, chronology, or numbers; but focuses on analogous lessons on divine ethics.

The average story – such as that of Hūd, Nūḥ (Noah), Ṣāliḥ, Shuʿayb (Jethro), Lūṭ (Lot), and others – goes something like this:

(1) God appoints the best person from a community to deliver a bold truth to them.

(2) The primary element of this truth is to expunge the self and the society of its idols – which are both its religious deities, and anything obeyed and exalted at the expense of God (including the ego and tyrannical social structures).

(3) The secondary element of this truth is usually an ethical prescription that is particular to the said community. In the case of Shuʿayb, it was to establish economic justice; in the case of Lūṭ, it was to tackle sodomy.

(4) This truth is said to be hardwired in us and in creation, and thus it is not just accepted at face value, but it is to be meditated upon and observed.

(5) Some accept this truth, and others reject it. Those who accept it become “Muslims” – submitters and adherents to God. Those who reject it deliberately out of hard-heartedness are “kuffār” – those who cover the truth willfully.

(6) The Muslims are saved from a life of ignominy and delivered in the Hereafter, while the kuffār are destroyed either in this life or the next.

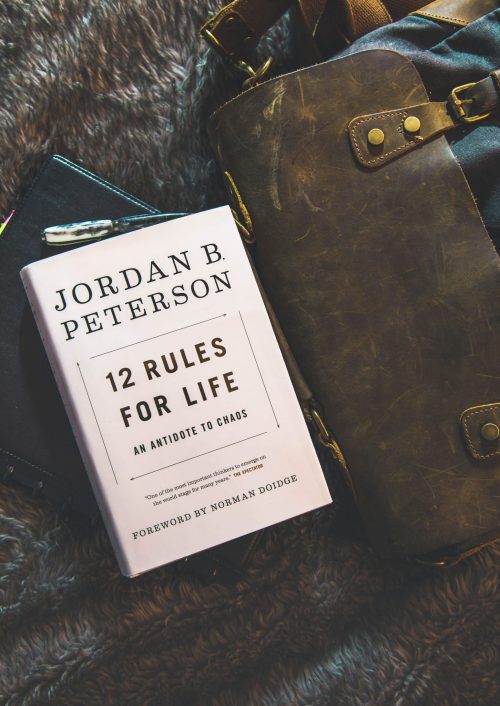

Jordan Peterson’s Best-Selling book “12 Rules for Life”

Islamic literature submits a few case studies for this dialectic – namely, ʿĀd, Thamūd, Sodom, Egypt, Babylon, the Himyarite kingdom, the Children of Israel, and the Jāhilī Arabs. Destruction is not spontaneous – in most of the above cases, it took years or even centuries for societies to devolve and eventually dissolve.

A number of modern Islamist thinkers – such as Sayyid Qutb and Ali Shariati – may have taken inspiration from Marxism, focusing on social and economic justice and revolutionary politics. Precedent was found in the concept of zakāt, the character of Abū Dharr, the policies of early Muslim rulers, and general references to social welfare and neighborly hospitality.

The Qur’an speaks of the social elite (malaʾ) in unfavorable terms in its seventh chapter, implying that it was the chiefs and the moneyed interests that would first reject sacred prescriptions. This is echoed in a narration where Abū Sufyān tells Emperor Heraclius that the followers of the Prophet Muhammad were poor; and Heraclius replies by saying that all the prophets were followed by the poor.[1] However, this should not be taken in dualistic terms, as divine sustenance (rizq) is viewed by the normative tradition as coming in many forms, and it is considered by Muslims to be another human test among many.

Furthermore, absolute equality is not possible. Not only are there too many human variables that would be factionalized – sex, race, class, education, age, IQ, upbringing, health, strength, height, weight, skills – but the Qur’an creates a hierarchy of applied gnosis. The Qur’an says that those who know are not equal to those who do not know (39:9). Adam’s authority was demonstrated through his knowledge of the names, which the angels did not have (2:30-34). Saul’s authority was also based on his intellect (2:247). The Hereafter itself is a hierarchy of ethics. This is in some contrast to Peterson’s argument that hierarchy is rooted in biology, because knowledge and praxis can transcend biological determinism in the same way that social institutions could restrain natural forces. Human societies thus need to define competence in light of knowledge by rewarding those who act on sound uses of their intellect (ʿaql).

Muslims can work towards proper social equity, and create systems that guarantee the rights of people, but equality of outcome is impossible and unjust. There is also no use to equality if two persons were equal but unhappy, equal but oppressed, or even equal but malevolent.

Another pillar of Peterson’s argument is that value judgments should not be applied to entire groups, but to individuals. This is in response to the idea that the bourgeoisie are malicious and the proletariat are good; and in extension, the idea that white heterosexual males are oppressors and the rest of the population are marginalized or oppressed. On one hand, Abrahamic religions express individual agency and accountability – the individual is much more than his accidents.

On the other hand, Israel, the Roman Catholic Church, the Body of Christ, and the Umma are all cosmic group concepts that definitively include and exclude people. In Islam, on the Day of Resurrection, everyone will be raised in disparate groups (99:6) with their leader (17:71). Leaders are the beloved role models of their followers, who emulate them consciously and subconsciously, and thus the Prophet Muhammad said, “A person will be in the company of those whom he loves.”[2] In a sense, a group can be judged by the heroes that it chooses, because those heroes have the characteristics that are worthy of the praise and emulation of the group. But since the intentions and actions of everyone differs, a holistic value judgment would still need to take the individual into account.

Lastly, Peterson critiqued Marx’s concept of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Peterson said that there is no reason why this new leadership wouldn’t become corrupt after assuming absolute power. Indeed, this Marxist idea is strangely utopian and even messianic for an atheist philosophy. Peterson takes a more pessimistic view, saying that we humans were built for trouble, and we would engage in creative destruction even if we were handed everything that we wanted.

This is in part reflected in a prophetic saying, “If a human had a valley of gold, he would want two valleys.”[3] But Peterson’s view – rooted again in biological determinism, or perhaps the Christian view that human nature is essentially evil – assumes that humans will always be insatiable and even destructive. The reality, however, is that socio-cultural, political, economic, and environmental variables all affect the crime rate; hence the right conditions can reduce human destructiveness.

As for the utility of individualist laissez-faire capitalism to this end: even if one were to claim that it brings down violent crime (even though China, for example, appears to have a far lower homicide rate than the United States),[4] capitalism has brought about new and unprecedented forms of destruction through ecological damage, the military-industrial complex, factory farming, private prisons, brain drain in the developing world, processed foods, dangerous new technologies, the sex industry, and other kinds of legal exploitation.

A free market must always be guided by rules. In the same way that regulations exist in business, ethical regulations need to be extended to prevent self-destructive behavior. Capitalist democracies cannot always create protocols against behaviors that are deeply ingrained in societies.

While capitalism has produced more wealth than any other system, quality of life is determined by more than just the accumulation of capital. A new German study suggests that Muslims have the highest life satisfaction in the world – even higher than Christians, Buddhists, and yogis.[5] Suicide rates in the Muslim world are generally lower even in comparison to wealthy European, North American, and East Asian countries.[6] In Islam, quiet of mind is found in the remembrance of God (13:28), and the good life is the product of good works (16:97).

Jordan Peterson speaks about the dominance hierarchy as a natural structure of competence. This social hierarchy is either climbed by demonstrations of merit, or through repression. Peterson’s implied argument about neoliberalism is that it is basically a model that rewards competence with hierarchical mobility; while communism is a system of oppression.

There is no doubt that the Prophet Muhammad was at the top of the dominance hierarchy in Arabia by the end of his life. Was that due to his competence or his tyranny? Using Peterson’s worldview, the normative Muslim would see nothing but merit from Muhammad. The view has weight as there is no standing evidence of forced conversion under him or his early followers.[7] His flight to Medina ended civil strife there, and he wrote a constitution that included other religious groups.[8] He issued a treaty with the polytheists at Ḥudaybiyya. He famously forgave his opponents when the Muslims marched back into Mecca.[9]

The overarching theme of Peterson’s Bible lectures was that creating order from chaos was a good, divine act which fits quite well with the narrative of the Prophet Muhammad took a chaotic society (Jāhiliyya) and set order into it. Not only did he “clean his room”, he inspired a civilization that brought dignity and prosperity to an otherwise peripheral people with little historical significance.

Slavoj Zizek

Despite Peterson’s Canadian origins, it felt that Zizek had the home-team advantage. He was almost never heckled by the audience, and he received louder cheering than his opponent. Downtown Toronto may be the most left-leaning place in the world, and while Zizek is not a typical liberal or activist, he would still receive a warmer welcome than his opponent, who is regularly deemed a sexist, homophobic, transphobic, racist Islamophobe. Whether these characterizations are accurate will not be the focus of this essay.

Slavoj Zizek claimed at the beginning of his discussion that both him and Peterson are shunned by liberal academia. While Zizek’s oddball personality may sometimes get him in trouble, a 2014 survey shows that sixty percent of American professors self-identify as liberal or far-left,[10] making Zizek’s views more palatable to most academics. Indeed, while attaining my degree in political science in Toronto, there was hardly a course I took where Marx’s views were not a prominent feature.

Of course, what is far more shunned than both Peterson’s Anglo classical liberalism and Zizek’s quasi-Marxism is a worldview rooted in the divine. To any traditional Muslim, Christian, Jew, or Hindu, sensory phenomena – which is the focus of academia – is just one aspect of the world. Its study would be akin to the study of the sewer system, without acknowledging who built this system, why it was built, where the matter is coming from, where it is going, and the world above it.

Zizek pointed out that China is economically successful, but this is in part due to capitalism. He acknowledged that China’s success is owed to its Confucianist harmoniousness and collectivism, which highlights the utility of cultural forces in politics and economics. Weber’s theory of the Protestant work ethic would be a Western example of how the values of a society could engender economic growth. Similarly, the spread of Islam would not have been possible without trade.

Zizek claimed that once tradition loses its power in society, one cannot return to it; and any attempt to return to it would just be a “postmodern fake”. This is an echo of Nietzsche’s “death of God” – that the Enlightenment broke the foundations of traditional religion, diminishing its authority in the modern day.

It is unclear if Nietzsche would have felt the same way about the Islamic civilization, which receives some praise in his works. But the idea that modernity or postmodernity has permanently diluted or destroyed tradition relies on a number of premises: namely, that science and reason are separate from religion, that secularism has wholly replaced traditionalism, and that people today are more capable of assessing the alleged superficiality of religion.

While the Enlightenment has caused the socio-political and economic influence of the Church to wane, the vast majority of people still believe in a Higher Power and the supernatural,[11] including most scientists.[12] In a sense, it can be argued that while organized religion is declining in the West, people are as religious as ever. Most modern Westerners are not atheists, but heretics: people who believe in a heterodoxic form of Judaeo-Christian religion.

While atheism, globalization, and the marketplace of ideas are features of modern life, they have arguably always been salient even in the pre-modern world. Yes, the strength of certain institutions may diminish, but the role of religion in ethics (even secular humanist ethics) is prominent. Regarding Zizek’s statement: “tradition” was never a monocultural force for us to “return” to, but it can always be a source of integrity that manifests at different levels of society.

Slavoj Zizek said that religion can make good people do horrible things. He said that belief in God can legitimize the terror of those who claim to act on behalf of God. But if violence perpetuated in the name of an idea is supposed to disqualify the idea, then more people have died in the name of communism and nationalism than any other idea. To be fair, Zizek affirmed that Stalinism, and ideologies in general, could make “decent people do horrible things.” But what if people simply use ideology and religion to mask their aggressive impulses?

Thereafter, the subject of suffering was brought up. Zizek said that one should not assume that his suffering is a by-product of his decency. From a naturalist perspective, suffering has no intrinsic value – it is seen entirely as accidental, or a painful injustice of society and nature.

The Abrahamic religions propose a spiritual function to suffering: it is a supernatural trial, punishment, process of purification, or a combination of all of the above. The way we conceptualize suffering is influenced by neurological factors, as well as cultural and educational factors.[13] Hence, a “no pain, no gain” approach to suffering may constructively expand the self rather than attack or destroy it.

While suffering is not a linear indicator of righteousness, the popular view in the Islamic tradition emphasizes that the righteous will endure more trials than others. When asked who is tried most severely, the Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said, “The prophets, then those most like them, then the most like them [and so on].”[14] This world, which is described as a “prison for the believers”,[15] is a type of purgatory that prepares the righteous for meeting with God.

This is not meant to be masochistic or sadistic in any way: suffering not to be glorified, rather the Islamic tradition takes many steps to restrict it; but the logical end of upholding an ideal is being accountable to it, even if it means that one must take a loss. In this sense, I agree with both Peterson and Zizek that the identitarian ideologues gloat their victimhood to a pathological degree. The Muslim is commonly encouraged to look at his problems as a storm in a teacup.

A particular “gotcha” moment has become a highlight in the debate. Zizek expressed that the alt-right invented the story of Cultural Marxism as the needed scapegoat, external enemy and source of civilizational grievance. Zizek does not see Marxism as a potent force in academia; and he challenged Peterson to provide examples of postmodern neo-Marxists in universities.

A pause by Peterson implied to the audience that he did not have an answer, but then he correctly proceeded to describe the role of Foucault and Derrida in recasting the “bourgeoisie vs. proletariat” frame into an “oppressor vs. oppressed” frame. Zizek actually agreed with Peterson’s comment, but he did not see the continuity of the identity politics of today with Marxism.

Many populists have certainly simplified their grievances into a global conspiracy involving elites, Jews, liberals, and academics, who simultaneously dominate “establishment” politics, mainstream media, and the universities, while waging an existential war on whites. What is clear is that there are no self-proclaimed “Cultural Marxists”. At the same time, the effects of Foucault’s ideas and the “Long March Through the Institutions”[16] on activism and socio-political institutions are real.

They have created an unforgiving culture that is fixated on power, perpetrators, and sabotaging dissent. The idea however that immigration policies are designed to destroy whiteness is absurd: immigration is a corrective to the West’s demographic and economic shortcomings. Mercy may be a small factor in the taking of refugees, but mercy is a civilizational merit, not a weakness.

Lastly, Zizek critiqued Peterson’s famous “clean your room” advice, which is designed to direct people toward personal growth before taking on the problems of society. Zizek argued that, sometimes, one’s life is in disorder due to the effect society has on it. He said that Peterson is a good example of someone who is simultaneously reordering his life and taking on civilizational issues.

Certainly, the Islamic concept of “enjoining in established virtues” (al-amr bil maʿrūf) and even jihād have inward and outward dimensions. But the “greater struggle” in normative Islam is the struggle with the self (nafs). Once the self is rectified, God promises to rectify people’s conditions (13:11). From this perspective, instilling a stronger sense of personal responsibility in today’s world is perhaps more important than partaking in protests and civil disobedience, even if both have their place.

Those whom we may protest are also people who are capable of introspection and reform; and Marxism and its liberal offshoots too often otherizes and dehumanizes the “oppressor” class. What the Abrahamic tradition offers is a genuine sense that a person can change, even if after penance.

Conclusions

The Islamic tradition has a lot to offer on life’s big questions. These points are simply the reflection of a young student, barely scratching the surface of complex issues. Islam’s dialectic, ethical tradition, and emphasis on personal accountability are original whilst also sharing many points in common with other Semitic and Aryan traditions and Greek philosophy.

While Slavoj Zizek and Jordan Peterson may cast Islam aside, it may soon become the world’s most popular paradigm. Unfortunately, Enlightenment values have perhaps permeated the views of most Muslims, and capitalism and socialism are dominant frames in today’s world; and thus it is vital for Muslim intellectuals to continue discussing the intersection between economics and ethics. Muslim institutions and ordinary folk need to do more to support initiatives that deal with such consequential issues. While the Titanic offers the bells and whistles of modernity, our focus should not waver from the Ark.

[1] Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 1, hadith 7, https://www.sunnah.com/bukhari/1/7

[2] Muhammad al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 78, hadith 194 https://sunnah.com/bukhari/78/194

[3] Ibid, Book 81, hadith 28 https://sunnah.com/bukhari/81/28

[4] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/vc.ihr.psrc.p5

[5] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-6908769/Muslims-highest-life-satisfaction-thanks-feeling-oneness.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_suicide_rate

[7] https://yaqeeninstitute.org/hassam-munir/did-islam-spread-by-the-sword-a-critical-look-at-forced-conversions/

[8] Moshe Gil and David Strassler. Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages, Brill pp. 21

[9] Joseph McDonald, Exploring Moral Injury in Sacred Texts, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 76

[10] Christopher Ingraham, “The dramatic shift among college professors that’s hurting students’ education”, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/01/11/the-dramatic-shift-among-college-professors-thats-hurting-students-education/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.aab155ece39d

[11] https://www.pewforum.org/2018/04/25/when-americans-say-they-believe-in-god-what-do-they-mean/

[12] https://www.pewforum.org/2009/11/05/scientists-and-belief/

[13] Noelia Bueno-Gómez, Conceptualizing suffering and pain, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5621131/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5621131/

[14] Muhammad b. Yazid b. Maja, Sunan Ibn Maja, Book 36, hadith 98, https://www.sunnah.com/ibnmajah/36/98

[15] Ibid, Book 37, hadith 4252 https://sunnah.com/urn/1292150

[16] Bilal Muhammad, Slide to the Left!, https://thedebateinitiative.com/2019/03/12/slide-to-the-left/