Conventional understandings of the psycho-emotional concept of ṣabr in Islam exacerbates the current mental health crisis in Muslim communities. Here is why and how we can take a more healing perspective of the term.

First Disclaimer: This essay is not a criticism of ṣabr in Islam per se. It is a critique of the Muslim communal understanding and the modern lived experience of ṣabr insofar as Muslim diaspora communities living in the West are concerned. In this piece, I want to offer a taxonomy of ṣabr that, to the best of my knowledge, is more in line with traditional understandings of the concept that are far more compassionate for the modern human condition.

Second Disclaimer: When I refer to stoic behavior or stoicism, I’m not referring to classical stoicism as a philosophy of personal ethics. The classical stoics did not advocate for suppression of emotions but rather acceptance and self-restraint, an attitude which is closer to more traditional approaches to ṣabr. Stoicism and stoic behavior, in its modern cultural and even lexical understanding (which I called stoic ṣabr) is more in line with what I outline as destructive behavior, denial and suppression of pain and emotions.

***

For Muslims, ṣabr is one of the greatest of human virtues. Prophetic traditions deem it as one of two parts of faith (īmān). Others call it the pinnacle of faith. Whatever way you may want to understand the term, it is a fundamental part of Islam regardless of sectarian affiliation.

Translations play a greater role than just rendering words to another language. The fact that it communicates the meaning of a source-language to its perceived equivalent in its target-language says a lot about how we understand important concepts and terms in their original languages. The semantic properties of our beliefs not only inform us of how to perceive the world, but more importantly how to act in it.

The Common Understanding of Ṣabr

Sabr is popularly translated as patience. By patience, it is commonly understood that one suffers without feeling anger, fear, or any other disruptive emotion. For many Muslim communities, the ṣābir (the subject who practices ṣabr) is essentially a stoic, one who endures hardship without showing feelings or complaining.

The stoic is thus the epitome of spiritual maturity. When dealing with pain and suffering, anything short of reacting with joy or at worst, internal indifference, is a defect of character and faith.

The semantic properties that Muslim communities give to ṣabr are not isolated and abstract musings, nor are they just private virtues that a certain few atomized individuals attain whom everyone tells stories about, they have profound implications on the normative expectations for acceptable behavior and more importantly, how trauma and mental illness are dealt with.

Below, I will be writing about the experiences of the communities I have lived in and how faulty these communities’ understanding of ṣabr have been used to exacerbate a very real and growing communal crisis of emotional and mental illness. I am by no means claiming that this approach to ṣabr is absolute, for I have seen some wonderful steps in the right direction in a handful of clusters. I am merely recounting my own experiences.

Encouraging the Suppression of Emotion and Pain

As a person who has been an active member of the Muslim community for two decades in North America, from the East Coast to the West Coast, I have witnessed how communally dominant understandings of ṣabr have been used to belittle and shame people suffering from complex post-traumatic stress disorder[1] (C-PTSD) and other forms of emotional and mental illnesses.[2]

I have encountered Muslim men who suffer from continuous and severe panic attacks and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) because they were raised by abusive addicts and they were sexually abused growing up as children. Yet, when they’ve sought help in the community for anxiety, their traumas were dismissed, and they were shamed for having weak faith. For many members of the community this is the reality of the religious life because a truly pious person cannot feel anxiety and depression.

They were urged to have ṣabr and reminded that their sufferings were nothing compared to what previous prophets and other saints went through. At best, people such as these Muslim men are prescribed a few prayers to solve their problems. If the prayers don’t work and the men complain, then it’s concluded that they don’t have ṣabr and that the prayers may not be working because they are sinners. At best, they are simply advised to have more ṣabr, i.e., suppress emotions even more and put greater effort in acting like everything is fine.

Although in the right circumstances the reminders of the sufferings of past saints are useful and even necessary, more often than not they send the following message: the pain you feel is not important, which ultimately means you as a person are not important. The pain then gets dismissed because it is perceived to be the result of your short-comings, sins, and weak faith. It is also implied that if you want to be a valued and respected member of the community, you need to bottle up your emotions and pretend that there is nothing wrong. The guilt trips that follow merely exacerbate desperation, loneliness, and mental illness.

This is not just a problem with Muslim communities, but one that befalls religious and secular communities alike. The job market places a prime value on people who are stoic, who, despite the tragedies in their lives, can “tough it out” and “power through”. This encouragement or indeed expectation of toughing it out and powering through, especially for men, only compounds the problem of ṣabr in Muslim communities. Men have it doubly worse for at least women’s mental health checkups are offered in many women’s work and university health centers. Men, unfortunately, often lack these resources and are further discouraged by society from expressing their emotions. More destructively, argued that this is the fault of conservatism and the patriarchy rather than a system that promotes certain forms of progressive politics that belittles, trivializes, and disenfranchises male suffering.

There are a number of incidences that come to my mind that drive this assertion of mine. Take the example of the American political scientist Warren Farrell and author of the book Boy Crisis. In the 1970s he was one of the strongest supporters of second-wave feminism. He regularly led conferences criticizing sexist systems of power that oppressed women. Yet along his career, he noticed the particularly egregious suffering of men in Western society that often went unnoticed. As a result, he began speaking and leading conferences that touched on male issues. To his own shock, feminist organizations stopped inviting him to conferences. As the purported father of the ‘men’s movement’ in America, disinvitations turned into vilification by the same groups he advocated for.

I can think of a number of personal experiences that were eye opening to me as well. As a mentor to a number of Muslim community members across America and Canada, I have visited many mental health institutions. Almost every single one that I have observed had women’s health groups and programs, yet whenever I inquired about men’s health programs, I was given a confused look and redirected towards therapists on ground. The same has applied to university services that are offered that enthusiastically promote programs for women’s physical and mental health, but nothing specific for men.

Perhaps another experience that has stood out to me was a conference I joined that was led by a prominent Muslim American feminist academic. In that speech, she had complained about her Muslim husband’s habit of bringing his friends to their basement to discuss religious and personal issues. Her response was that she felt disenfranchised at this “man cave” her husband and his friends held. She spoke of her battle to join in these groups as part of her quest to beat patriarchy in our community. At this point I am not taking issue with her concerns, but what I find troublesome was her later advocacy for Muslim women’s spaces as “safe spaces” rather than “woman caves.” Women could have their spaces where they could comfortably and freely express themselves outside of the male gaze (including in her home), but this privilege was to be denied to men because it represented patriarchy.

Coming back from my little digression, it goes without saying that in a modern age where most people have lost their social connections and are dominated by chronic isolation and loneliness, existential despair becomes the most likely outcome. This is true for both men and women.

Ṣabr and Compounding Mental Illness

The adoption of stoic ṣabr, that is, sucking it up and toughing it out, has devastating health consequences. Gabor Maté is a Canadian physician who was the head of the palliative care department at Vancouver Hospital. He has a special interest in trauma (especially childhood trauma) and how they have lifelong consequences on addiction, ADHD and the onset of autoimmune diseases.

Maté observes how suppression or repression of emotions do not simply disappear but are stored in the body. Over the time, although we may consciously suppress or ignore heavy emotions (especially those that are the result of trauma) the body will eventually say no which often end up in the body rebelling through long cycles of physical illnesses like cancer and autoimmune diseases like ALS, arthritis or ulcerative colitis.

Maté’s observations are not unique nor are they discoveries. His observations are part of a current slew of evidenced-based push back against decades of mainstream psychological and psychiatric establishment denial of the trauma-and-disease-connection. Overwhelming evidence by scientists in the field such as Bessel van der Kolk, Bruce D. Perry and more importantly the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) by Kaiser Permanente and the CDC demonstrates how severe stress and trauma, especially childhood developmental trauma, can be directly linked to the onset of severe mental and physical illnesses in later adulthood even including the onset of Alzheimer’s in later stages of life. The more adverse childhood experiences, the higher the risk of disease and early death.

Anxiety and depression can be results of lifestyle and behavioral choices. They can also be the result of circumstances such as the loss of a loved one or a child. They can also be the result of physical and biochemical ailments. For example, one of my close friends suffered from chronic anxiety who was shamed and advised by the community to have ṣabr but later found out that his anxiety was the result of a disease and dysfunction in the liver. Sticking to the injunction to ṣabr and ignoring the problem could have cost him his life. Oftentimes, they are a mix of all of these things.

Anxiety and depression can also be the result of severe stress and trauma. The problem with this kind of anxiety and depression (and other their other forms), is that mental illness is not just a problem of the mind but a physiological one. Trauma-based anxiety can be embedded in our bodies. They are ingrained in our procedural memories. As Peter A. Levine points out, even when we consciously don’t remember trauma, our bodies visibly remember. They thereby manifest through survival reactions. Even though the traumatized Muslim subject may consciously act stoic, his body is likely to rebel in the short or long term. Although worry is a problem in the thoughts, anxiety as an emotion is a problem of the body. It can be observed in brain scans in the amygdala and the hippocampus. It reveals itself through headaches, migraines, insomnia, hypertension, backpain, digestive and cardiovascular problems or what have you. Some of these issues can later become chronic even for the most stoic of people.

We have all experienced how our procedural memories can derail us against our will especially when we are not paying attention. We have all driven towards our work place out of habit when we intended to go elsewhere. Many of us get the dates wrong after the New Year. Procedural memories are much more than that of course. We rely on them to walk, eat, drink, or go to the bathroom. We don’t consciously think of them, but they guide so much of our lives. As Levine points out, procedural memories are “deeply embodied resources in the forward movement of our lives.”

When trauma happens to us, we may try to forget, we may try to suppress them, but our bodies visibly remember them. They are the survival reactions of our anatomy that impact and impair our minds and our abilities to make proper moral judgments.

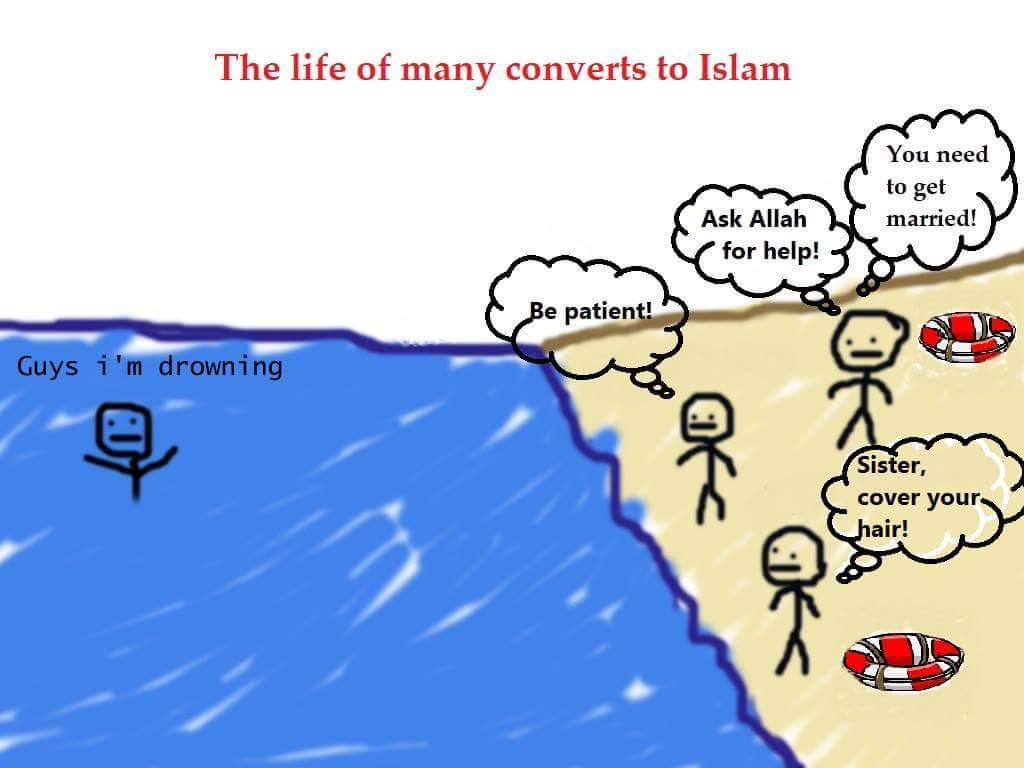

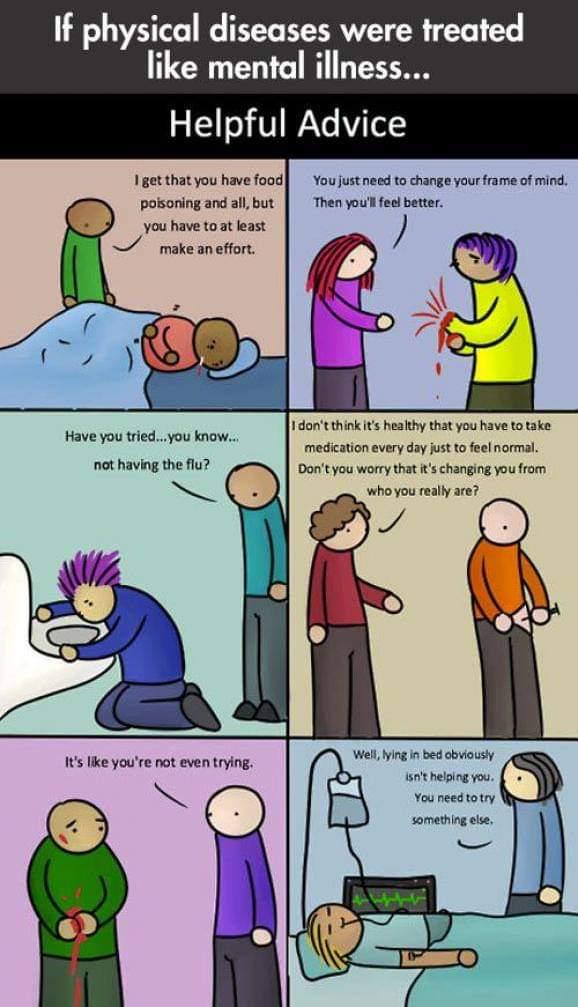

The encouragement to ṣabr, which is erroneously understood as being stoic and only supplicating to God in the face of trauma is one of the greatest disservices the community has done for those who publicly and privately suffer from mental and emotional illness for it does nothing but compound the problem. When someone breaks a leg or is diagnosed with cancer, we ask the afflicted person to pray but also seek professional help. When a person suffers from mental illness, it is assumed a priori that it is a defect in character and religiosity, that is, at least until the person making the assumption is also afflicted with mental illness. As such, there seems to be a double standard where Muslims claim Islam is a faith and actions religion, but on the issue of mental health, they act like it is a faith-only religion.

Suggestions on How to Better Understand and Approach Ṣabr

The first and most obvious place to look at for the semantic properties of a word are premodern lexicons. Ibn Manẓūr (d. 1311 AD) traces ṣabr’s origins to restraining and binding a person in order to slay him (nasb al-insān lil-qatl and hence ṣabr al-insān ʿala al-qatl).[3] He also traces this sense to the treatment of animals in traditions where the Prophet Muḥammad forbade the castration of animals (tuṣbar al-rūḥ), an Arabian practice that was used to help tame and better restrain animals, especially horses and camels. It also refers to the forbidden practice of restraining animals and throwing objects at it till it dies.[4]

In terms of personal character and ethical behavior, ibn Manẓūr traces the meaning to restraining oneself in the midst of apprehension or affliction (al-ṣabr ḥabs al-nafs ʿind al-jazaʿ which clarifies the understanding of ṣabara fulān ʿind al-muṣībah).[5] It is also when one is moderate and deliberate (ḥalīm) as in the sense when God is ṣabūr where he does not rush towards a recalcitrant person with revenge.[6]

According ibn Manẓūr, this sense can also be observed in the Qur’an which advises the faithful in the following way: content yourself with those who supplicate to their Lord…(Q18:28) where aṣbir nafsaka takes the meaning of confining oneself with those who supplicate to their lord. The verse and those who enjoin one another to ṣabr (Q109:3) feeds into the meaning of those who persevere in obeying God and restrain themselves from disobeying him (tawāṣū bi-al-ṣabr ʿala ṭāʿat Allāh wa al-ṣabr ʿala al-dukhūl fī maʿāṣīh).[7] Perseverance in obeying God can thus take the meaning of also confining oneself to his obedience.

In its overall Qur’ānic sense, the Qur’ānic lexicographer al-Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī (d. 422/1031) begins with the meaning of restraining someone or something so that there is no escape. It refers to restraining and confining oneself (ḥabs al-nafs) with the dictates of the intellect and revealed law (al-āql wa al-sharʿ).[8] Thus, when one is persevering for God’s sake, one is confining oneself to God’s obedience and struggling against carnal desires (aḥbisū anfusikum ʿala al-ʿibādah wa jāhidū ahwākum).[9] This can include perseverance during war where it would be sinful to turn back and run away (Q8:66). Similarly, it can include persevering in upholding one’s prayer (Q2:41, 148).

The first indication that popular understandings of ṣabr are not compatible with early, particularly premodern Muslim practice are what the source-texts tell us about the lived experienced of the Prophet Muhammad.

Take for instance the following tradition taken from Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī:

عَنْ أَنَسِ بْنِ مَالِكٍ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ قَالَ دَخَلْنَا مَعَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ عَلَى أَبِي سَيْفٍ الْقَيْنِ وَكَانَ ظِئْرًا لِإِبْرَاهِيمَ عَلَيْهِ السَّلَام فَأَخَذَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ إِبْرَاهِيمَ فَقَبَّلَهُ وَشَمَّهُ ثُمَّ دَخَلْنَا عَلَيْهِ بَعْدَ ذَلِكَ وَإِبْرَاهِيمُ يَجُودُ بِنَفْسِهِ فَجَعَلَتْ عَيْنَا رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ تَذْرِفَانِ فَقَالَ لَهُ عَبْدُ الرَّحْمَنِ بْنُ عَوْفٍ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهُ وَأَنْتَ يَا رَسُولَ اللَّهِ فَقَالَ يَا ابْنَ عَوْفٍ إِنَّهَا رَحْمَةٌ ثُمَّ أَتْبَعَهَا بِأُخْرَى فَقَالَ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ إِنَّ الْعَيْنَ تَدْمَعُ وَالْقَلْبَ يَحْزَنُ وَلَا نَقُولُ إِلَّا مَا يَرْضَى رَبُّنَا وَإِنَّا بِفِرَاقِكَ يَا إِبْرَاهِيمُ لَمَحْزُونُونَ

Anas ibn Malik reported: We entered the house of Abu Sayf along with the Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, who was the husband of Ibrahim’s wet-nurse, upon him be peace. The Prophet took hold of Ibrahim, kissed him, and smelled him. Then, we entered after that as Ibrahim was breathing his last breaths. It made the eyes of the Prophet shed tears. Abdur Rahman ibn Awf said, “Even you, O Messenger of Allah?” The Prophet said, “O Ibn Awf, this is mercy.” Then, the Prophet wept some more and he said, “Verily, the eyes shed tears and the heart is grieved, but we will not say anything except what is pleasing to our Lord. We are saddened by your departure, O Ibrahim.”

A few pointers here can be extracted. We find that even during the time of the Prophet, there were people who thought people of high patience and faith could not cry. Yet the Prophet’s practice showed otherwise. He did not bottle up his emotions but rather accepted his grief and expressed it. He acknowledged that there was nothing wrong with shedding tears and grieving but to the contrary, it was a natural part of the human condition. What was frowned upon was lacking self-restraint, that is, in saying or doing things that would be sinful and displeasing to God. We can deduce here that in Prophetic practice, restraint from grieving and shedding tears was not what was required of ṣabr, but the restraint against sin in the midst of strongly-felt emotions.

We can naturally extend this to any other kind of natural feeling, such as fear, anger or what have you. Ṣabr does not entail that the Muslim subject ignore or suppress his or her feelings, it entails that one should restrain from acting out in a way that is sinful when these emotions are felt.

On Other Levels of Ṣabr

The term may also refer to an acceptance of fate (amor fati) as in the case when Jacob, upon hearing of the supposed death of his son Joseph, said “resignation is beautiful” (fa-ṣabru jamīl) (Q12:18). Yet despite accepting his son’s death or the realization of his sons’ deceit and lie of Joseph’s death as other commentators state, the story holds that he mourned for Joseph for decades. Q12:84 states that his eyes turned white with grief and was choked with anguish (abyaḍat ʿaynāhu min al-ḥuzn fa-huwa kaẓīm) (Q12:84). Some translators interpret kaẓīm as suppressed grief[10], but that does not follow the verse contextually for if he had suppressed his anguish why would his sons notice his grief that was apparently ruining his health? (Q12:83). Arabic lexicographers define kaẓīm as makrūb, meaning grieved and sorrowful.[11] Kaẓīm also holds the sense of constriction (as in kāẓim when someone restrains showing anger) and within this context it may hold some semblance to depression. If the word does take a sense of repressing grief, it is only in the context of Jacob repressing his complaints in front of his sons so as to express them to God exclusively as Q12:86 may indicate.[12] Similarly, it may also mean that he restrained himself from acting in a way that would be displeasing to God. Whatever the term may indicate, we know that kaẓīm is not suppressing emotional grief and sorrow but allowing the acceptance, feeling and expression of them for as long as necessary as it was the case for Jacob in the Qur’anic narrative.

Varying Capacity for Ṣabr

The capacity and levels of ṣabr varies from person to person. As the human soul matures, the propensity to equanimity increases. As equanimity, emotional balance and spiritual wholeness increase, the capacity for ṣabr also widens. Not only is ṣabr not an act of denying and repressing emotions, the acceptance, feeling and release of emotions is necessary in order to have ṣabr. Take for instance the following passage of the eight century Muslim saint Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765 AD) on grief and having lost his son Ismāʿīl (d. after 755 AD) to illness:

لَمّا حَضَرَ اِسماعیلَ بنَ جعفر الصادق الوفاةُ.نَظَر الناسُ اِلَی الصّادِقِ جَزَعاً یَدخُلُ مَرَّةً وَ یخرج اُخری،وَ یَقُومُ مَرَةً وَ یَقعُدُ اُخری،فَلَمّا تَوَفّی اسماعیلُ دَخَلَ الصّادِقُ اِلَی بَیتِهِ وَ لَبِسَ اَنظَفَ ثیابِهِ وَ سَرَّحَ شَعرَهُ، وَ جاءَ اِلی مَجلِسِهِ،فَجَلَسَ ساکِتاً عَنِ المُصیبَةِ کَاَن لَم یُصب بِمُصیَبَةٍ، فَقیلَ لَهُ ذلِکَ،فَقالَ: اِنّا اَهلٌ نُطیعُ اللهَ فیما اَحَبّ، وَ نَساَلُهُ ما تَحِبّ وَ اِذا فَعَلَ ما تُحِبُّ شَکَرنا،وَاذا فَعَلَ بِنا ما نِکُرهُ رَضینا

When Ismāʿīl neared death the people looked to al-Sādiq distraught with grief (jazʿa). A man would enter and another would exit. One would stand and another would sit. When Ismāʿīl died al-Sādiq entered his home and he was wearing his cleanest clothing and combed his hair and went to his majlis in silence from the tragedy. He was not stricken by tragedy. It was then mentioned to him for which he said: verily we are a people who obey God in what He loves, and we ask Him for what He loves. So when He does what He loves we thank him. When He does what we dislike [the death of my son], we are content.[13]

Although the feat of contentment so shortly after the death a child is humanly uncommon and the result of an extraordinary level of saintliness, even at this state al-Ṣadiq’s acceptance and peace with his tragedy was preceded by grief and anxiety. It may be said that the feeling and expression of grief, not its suppression, was necessary for emotional equanimity and the acceptance of a difficult fate. Take the following tradition as another example:

حدثنا الحسين بن أحمد بن إدريس (رحمه الله)، قال: حدثنا أبي، قال: حدثنا أحمد بن محمد بن عيسى، قال: حدثنا العباس بن معروف، عن محمد بن سهل البحراني، رفعه إلى أبي عبد الله الصادق جعفر بن محمد (عليه السلام)، قال: البكاءون خمسة: آدم، ويعقوب، ويوسف، وفاطمة بنت محمد (صلى الله عليه وآله)، وعلي ابن الحسين (عليهما السلام).

فأما آدم فبكى على الجنة حتى صار في خديه أمثال الاودية، وأما يعقوب فبكى على يوسف حتى ذهب بصره، وحتى قيل له (تالله تفتؤا تذكر يوسف حتى تكون حرضا أو تكون من الهالكين)).

وأما يوسف فبكى على يعقوب حتى تأذى به أهل السجن، فقالوا: إما أن تبكي بالنهار وتسكت بالليل، وإما أنا تبكي بالليل وتسكت بالنهار، فصالحهم على واحد منهما.

وأما فاطمة بنت محمد (صلى الله عليه وآله)، فبكت على رسول الله (صلى الله عليه وآله) حتى تأذى بها أهل المدينة، وقالوا لها: قد آذيتنا بكثرة بكائك، فكانت تخرج إلى المقابر مقابر الشهداء فتبكي حتى تقضي حاجتها ثم تنصرف، وأما علي بن الحسين فبكى على الحسين (عليهما السلام) عشرين سنة أو أربعين سنة، وما وضع بين يديه طعام إلا بكى، حتى قال له مولى له: جعلت فداك يا بن رسول الله، إني أخاف عليك أن تكون من الهالكين. قال: إنما أشكو بثي وحزني إلى الله، وأعلم من الله مالا تعلمون، إني لم أذكر مصرع بني فاطمة إلا خنقتني لذلك عبرة).

Al-Ḥusayn b. Aḥmad b. Idrīs narrated to us. He said: My father narrated to us. He said: Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. ʿIsā narrated to us. He said: al-ʿAbbās b. Maʿrūf narrated to us from Muḥammad b. Sahl al-Bahrānī, who traced it to Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Ṣādiq Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad (ʿa). He said: Those who have wept [excessively] are five – Adam, Yaʿqub, Yūsuf, Fāṭima bt. Muḥammad and ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn (ʿa).

As to Adam, he wept over Paradise until his cheeks became like valleys (i.e., curved, sunk in). As to Yaʿqub, he wept over Yusuf until his vision left and until he was told: “By God! You shall not cease to remember Yūsuf until you become sick to the hilt or you are of those who perish” (12:85).

As to Yūsuf, he wept over Yaʿqub until the inhabitants of the prison were hurt by it and they said: Either you weep by day and be silent at night or that you weep by night and be silent in the daytime. So, he agreed to one of those two with them.

As to Fāṭima bt. Muḥammad, she wept over the Messenger of God (ṣ) until the people of Medina were troubled due to it. And they said to her: “You give us trouble through the excess of your crying.” So, she went out towards the graves of the martyrs and wept until her need was accomplished; then she would depart.

And as to ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn, he wept over al-Ḥusayn for twenty years or forty years. And food would not be placed in front of him, but he would weep until a retainer of his said to him: “May I be ransomed for you, O son of the Messenger of God! I fear for you lest you be of those who perish (i.e. due to the excessive crying and lack of nutrition).” He said: “I only complain of my sorrow and my grief to God, and I know from God what you know not. Surely, I do not remember the perdition of the children of Fatima but that I am choked with tears because of that.”[14]

In this tradition, we see some discomfort at the grief and sorrow of some prophets and saints. Yet the tradition seems to indicate that emotions like grief over the suffering of having lost a loved one (and perhaps other forms of suffering in the world) are not only saintly and prophetic practices, but their expression may draw one closer to God as long as sinful behavior is not involved.

Some Concluding Remarks

Before I conclude this article it is important that I delve in a few corollaries of ṣabr. In studying the various discursive traditions of Islam, I have understood ṣabr as a practice that feeds into the development and maturity of the human soul. Self-restraint is not just restraint from the normative sins of Islam, but more fundamentally restraint from shaming and blaming which in reality are manifestations of denial. The act of denial, as in shaming and blaming, in light of difficult circumstances is running away from one’s own emotions, feelings, reality and brokenness. It is a refusal to deal with difficult interior circumstances that only get compounded in severity the more one denies their reality. In this view, it may be said that suppressing one’s emotions can be an act of non-ṣabr.

This denial through shaming and blaming also leads to a more precarious problem for the human condition, namely loneliness and disconnect from oneself and thus God. Hannah Arendt saw loneliness not just a disconnect from others, but primarily a disconnect from oneself and for her, it was societies with rampant disconnection to the self and rampant loneliness that gave way to the rise of totalitarianism.

It is this disconnect that leads to various toxic human addictions and attachments. There is a popular notion that assumes that the opposite of addiction is sobriety, but that is false. The opposite of addiction is connection, namely connection to oneself, others, the world and ultimately God. The act of recovery from addiction is not sobriety (real permanent sobriety is only a by-product of recovery), but it is to regain something that was lost, stolen and destroyed. Recovery is regaining one’s connection to the self which was destroyed in life, and the putting back of pieces that were taken apart.

Hence ṣabr requires that instead of immersing oneself in addictions and bad habits, one turns back and reconnects with one’s soul. Part of this reconnection is not running away from one’s emotions and suffering, but to accept them, feel them, have compassion towards them and finally surrender to God without victimizing oneself.

As one surrenders, transforms, and becomes whole through the integration of emotions, chaotic emotions stabilize and become harmonized in the heart. Hard emotions will always exist, but they come and go as clouds around a mountain, the mountain being the mature human soul in the wholistic process of ṣabr.

The fifth step of ACA’s (Adult Children of Alcoholics) 12 Step Program teaches us that depression and anxiety are often the result of unexpressed grief, a life and/or childhood that was lost due to abuse from the world. Grief is allowing the inner child and inner soul in the adult to properly process its emotions and heal from trauma. Muslim traditions also teach us various ontological exercises to help us spiritually heal. These exercises include prayer, repentance, meditation, and other spiritual exercises. But as far as I have understood the tradition, no practice is understood to be as powerful in connecting one with God and as purifying to the soul as grief is. Grief is not only grief over sin, but grief over the pains and suffering of this fallen and broken world:

قَالَ حَدَّثَنِی جَعْفَرُ بْنُ یَحْیَى الْخُزَاعِیُّ عَنْ أَبِیهِ قَالَ دَخَلْتُ مَعَ أَبِی عَبْدِ اللَّهِ ع عَلَى بَعْضِ مَوَالِیهِ یَعُودُهُ فَرَأَیْتُ الرَّجُلَ یُکْثِرُ مِنْ قَوْلِ آهِ فَقُلْتُ لَهُ یَا أَخِی اذْکُرْ رَبَّکَ وَ اسْتَغِثْ بِهِ فَقَالَ أَبُو عَبْدِ اللَّهِ ع إِنَّ آهِ اسْمٌ مِنْ أَسْمَاءِ اللَّهِ عَزَّ وَ جَلَّ فَمَنْ قَالَ آهِ فَقَدِ اسْتَغَاثَ بِاللَّهِ تَبَارَکَ وَ تَعَالَى

Jaʿfar b. Yaḥya al-Khuzāʿī narrates from his father the following: I was with Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (ʿa) visiting one of his followers and friends. [Upon visiting him,] I saw the man repeatedly saying “Ah!” [out of pain] so I told him “O brother, remember your Lord and beseech His help [instead of making sounds of pain].” [Upon hearing this,] al-Ṣādiq said: “Ah!” is a Name among the Names of God (Exalted is He!) and whoever says [or cries out] “Ah!” has beseeched God (Blessed and Exalted is He!).[15]

Healing and indeed salvation are not found in the denial, suppression or running away from pain, suffering and grief as popular illusions of ṣabr hold – no – grief, pain and other human emotions are vehicles for rediscovering God’s presence in the consciousness of the human heart. God is not only found in one’s tranquility and happiness, but also in one’s suffering and grief.

[1] C-PTSD differs from PTSD in that the latter usually refers to single event trauma, whereas C-PTSD refers to repeated trauma over months or years such as continued childhood abuse, marital abuse etc. For more on this topic, see the following Healthline article.

[2] I am aware that some approaches do not like the term mental illness. Thomas S. Szasz argues that labeling traumas as mental illnesses assumes that they are exogenous forces to be medicated with and belittles them as psychosocial realities.

[3] Muḥammad b. Mukarram Ibn Manẓūr, Lisān al-‘Arab, 15 vols. (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1414/1993), IV, 437.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 438.

[6] Ibid., 437.

[7] Ibid., 439.

[8] Ḥusayn b. Muḥammad al-Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī, Mufradāt Alfāẓ al-Qurʾān, ed. Ṣafwān ʿAdnān Dāwūdī (Beirut: Dār al-Qalam, 1412/1992), 474.

[9] Ibid.

[10] See for example Ali Quli Qara’i’s translation.

[11] Khalīl b. Aḥmad al-Farāhidī, Kitāb al-ʿAyn, 9 vols (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyah, 2013), IV, 34.

[12] See for example al-Faḍl b. al-Ḥasan al-Ṭabrisī, Majmaʿ al-Bayān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān, 10 vols., ed. Muḥammad Javād Balāghī (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Nāṣir-i Khusraw, 1372 H.Sh/1993), V, 394.

[13] Warrām b. Abī Fāris, Majmūʿat Warrām, 2 vols. (Qum: Maktabah-yi Faqīh, 1410/[1989/1990]), II, 253.

[14] Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Bābūyah (al-Shaykh al-Ṣadūq), al-ʾAmālī (Tehran: Kitābchī, 1376/1998), 141. I would like to thank my colleague Bilal Muhammad who offered me this tradition already pre-translated by himself thus saving me the effort and time!

[15] Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Bābūyah (al-Shaykh al-Ṣadūq), Kitāb al-Tawḥīd, ed. Hāshim Ḥusaynī (Qum: Jāmiʾyi Mudarrisīn, 1398/1978), 219.